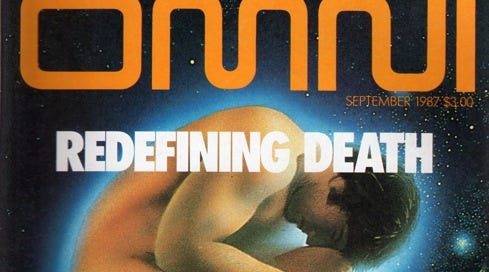

"Last Rights" an article from OMNI Magazine's September 1987 Issue

Title Theme for This Issue: "REDEFINING DEATH"

TITLE THEME: REDEFINING DEATH

This article has been typed and published to preserve it for a wider audience. I hand-typed the article using this .pdf upload as a reference. It's a fairly low quality scan missing a lot of detail, so expect some grammatical and punctuation errors.

Some choice cut phrases were bolded and italicized by me. I have also added URL's to noteworthy terms which readers would do well to research.

Enjoy your "Last Rights" and Total Fucking "Cognitive Death", You Single-Celled Units Trapped Inside Our Online Vegetative Egregore.

Smile and Remember:

"Destroy the brain stem and you abandon all hope of survival."

Last Rights

BY KATHLEEN STEIN

PAINTING BY MICHEL HENRICOT

On his back, eyes shut, breathing rhythmically, R.H - six three, 170 pounds - is a handsome man. Yet even one admires the strong lines of his body, surgeons with scalpels incise the skin and muscle of his chest and abdomen with long sure strokes. Using a small electric saw, they cleave the sternum as easily at if it were made of balsa. There is seriously (sp?)..

.. little blood, but there's a certain amount of dissarray in the operating room (O.R) when as many as eight doctors have their hands and arms inside the cadaver, working quickling to disconnect the organs from their many vessels.

Rib cage and thoracic cavity and splayed open and viscera held back with metal retractors known as iron interns. The organs reveal a marvelous power as when someone lifts the hood of a fine car and sees the frictionless workings of a precision-tuned engine. This engine is awesome - glistening, organic, wet. Aesthetically the liver is most pleasing, resembling some lustrous sea creature, smooth and supple with sharply defined edges. But a surgical error contaminates it. As a result the liver loses its silkiness and definition, turning from coral pink to meat market purple. The surgeons push the organ aside and struggling with their disappointment, proceed.

After another hour the kidneys - bean shapes that fit heftily in the surgeon's palm - are lifted out with ureters still attached.

R. H's heart suddenly begins an agitated dance, speeding from 100 to 200 beats a minute. The surgeons, alarmed, quiet it with a jolt of electricity from defibrilating paddles. Two hours later it too is removed and slipped into a stainless steel bowl full of saline solution.

As soon as each organ comes out, it is carefully packed in an Igloo Playmate full of dry ice and rushed to a waiting helicopter for delivery to a distant transplant team. Finally after the major organs are removed, a blond-haired surgeon from New York's Columbia Presbyterian Medical Center, his eyes rimmed by dark circles tells the anesthetist to disconnect the IVs and turn off the respirator.

A week earlier an aneurysm had ruptured R.H's brain - virtually ripping apart his cerebrum. Following clinical tests and electroencephalogram (EEG), physicians at Good Samaritan Hospital in Suffern, New York, declared him brain dead. It was his birthday, he was or would have been forty-two.

As I stood at his bedside in the intensive care unit (ICU) earlier that day, two perceptions fought in my mind. First: how could he be dead? He looked so full of life. There wasn't a mark on him. His thick light-brown hair was tousled, as if he'd just come in from a basketball game with the guys. His carotid artery pulsed with blood - his heart rate was nearly normal. The urine bag at the side of the bed filled regularly and was replaced. And secondly: an intellectual observation. He was obviously very dead. The blood oxygen, and nutrients per-fusing his body were all driven by the machines surrounding him.

There was something else, a more subliminal confirmation, subtle cues signalling that no one - no spirit? - was there. Lifting his arm, which was just slightly cool, i felt only a flaccid, lifeless weight.

And yet.... I wanted to whisper, so as not to wake him.

R.H is a late-twentieth century corpse - one of a new class of dead people created by medical technology. The 'beating heart cadavers' or neo-morts as these dead are sometimes called - have cells, tissues, organs and organ systems that can be kept alive several days by elaborate life support systems long after the brains have ceased functioning.

I first began to realize that the big sleep was no longer a simple state when I was researching material on the future of death for a book edited by Arthur C. Clarke. In the midst of scenarios about holographic mauloseums and near-death-experience cults, I found that the future, as they say, is already with us.

Since history's beginnings, the classical sign of death was when heart and lungs stopped. 'Brain death' is only about 20 years old - the offspring of the ICU and its advanced life support technologies. Even as we struggle with brain death, the concept is being modified. Bioethicists and members of the medical profession think the definition of death should encompass not only those who have no brain functions (the brain dead) but also those who have lost consciousness (the cognitive dead), "lost souls" who linger mindlessly in what are called persistent vegetative states. Society has to confront again some basic philosophical questions; what it means to be alive, to be a person, to have a mind. Before attempting to address those issues, here is a brief neo death lexicon.

Brain death. Very simply, this describes a state in which no part of the brain functions. Once a person is brain dead, he is dead: period. His body can be maintained artificially on a respirator only hours or at most, several days until cardiac arrest.

Persistent vegetative state. In brain death, the whole brain is destroyed. The brain stem - a primitive region that connects the brain to the spinal cord, is usually intact or mostly intact. A person with his brain stem intact is capable of stereotypical reflex functions - breathing, sleeping, digesting food - but he will be incapable of thought or even of any awareness of the world around him. A person can remain in this state for years.

Cognitive death. A number of bioethicists, philosophers, and MDs are beginning to contemplate expanding the definition of death to include people in persistent vegetative states - individuals who have lost their intellect, memory, speech and awareness of self or environment.

When I started my new death investigation, an MD friend said 'You've got to talk to Julie Korein, he wrote the book on brain death.' Julius Korein is professor of neurology at New York University School of Medicine, chief of Bellevue Hospital's EEG lab, and chairman of the biomedical ethics committee at Bellevue. A kind of tough guy with a spiky, intense personality, he moves and talks in swift bursts of energy. At first Korein seemed annoyed, even suspicious at being interviewed. 'Frankly, I'm sick to death of death,' he announced when I first met him. Soon though, he was supplying books, papers, and his time. Korein is currently investigating the 'beginning of brain life' in the fetus. Going full circle as it were.

"There is no moment of death," he says. The moment of death is a legal construct for matter of probate. As an example Korein cites a famous case of a husband and wife who were killed when their car was hit by a train. The body of one was crushed completely on impact - the other, decapitated. For the will, it was necessary to ascertain which one died first. The lawyers argued that it was the crushed spouse. As long as the other's head was spewing blood from the neck, it was deemed 'alive.' But even concerning the obliterated woman, Korein goes on, you can say, well, there were fractions of seconds before the whole person broke down and she died. So maybe the moment of death was fifty nanoseconds later.

'Look at cardiovascular death. The heart stops. The doctor listens to the chest. Was that the moment of death? With modern equipment you can detect signs of electrical activity in the heart forty minutes after it has stopped beating. The moment of death is fiction.'

I persist. Many people would say the moment of death is when the soul leaves the body. 'When does that happen?,' Korein attacks the idea. 'Let's assume there's a soul. When does it exit? When the heart stops? When the brain stops? When the reticular formation, the brain's arousal system, stops? Does it exit all at once - an instantaneous thing, or gradually? If gradually, then there's no moment of death!

In 1975 Korein was the expert witness in the Karen Ann Quinlan trial in which the family sued to have the life support system removed from the young woman. It was his testimony more than anything else that brought about a ruling in favor of the family - that Quinlan suffering permanent loss of higher functions, could be removed from the respirator. Quinlan had become comatose after ingesting a mixture of drugs and alcohol at a party.

During the trial one common misconception was that Quinlan was brain dead. 'She was never brain dead." Korein is irritated. 'At that time and even today people talk about her as brain dead. But she never met the criteria.' One of the criteria specifies that the brain stem no longer functions. There is no brain death without brain stem death, and in adults, brain stem death means that cardiac death inexorably follows within hours or days. Quinlan always had brain stem function.

The brain stem is the keystone of the central nervous system (CNS), the direct hookup to the spinal cord on one end and the cortex on the other. 'It is in every sense the ultimate site of 'Life's Little Candle'' says The Human Brain Coloring Book. Although it makes up only one tenth of the CNS, it controls the activities basic to existence; the autonomic - vegetatitve - functions. Destroy the brain stem and you abandon all hope of survival.

Korein was on the stand more than four hours. As a witness, he had to instruct the courtoom in the workings and malfunctions of the entire brain. he told them Quinlan was not brain dead. She had EEG activity in spite of massive damage to her cerebral hemispheres. And, he testified, she might breathe spontaneously off the respirator. And as the world knows, she continued breathing. Until her death from infection nine years later, she remained tethered to the life-supporting nutrition-hydration tube.

Soon after the Quinlan trial, Korein chaired an international conference to discuss research on brain death that had been ongoing from the late Sixties. And from that conference came the book Brain Death: Interrelated Medical and Social Issues. That text helped lift the fog of confusion enveloping doctors who were diagnosing the states of respirator-maintained patients. The book defined brain death clearly. The criteria included total unresponsiveness and lack of movement, no brain stem reflexes (having fixed, dilated pupils for example) and inability to breathe without a respirator. For confirmation, many neuorological tests were also encouraged to exclude the possibility of drug intoxication or hypothermia, conditions that can mimic brain death. Always there was the overriding rule: It is permissible to err only on the side of diagnosing a dead brain as alive.

in 1981, largely because of the work of Korein and many other neurologists, the President's Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and Biomedicine and Behavioral Science proposed as statute the Uniforn Determination of Death Act, which read "An individual who has sustained either (1) irreversible cessation of circulatory and respiratory functions, or (2) irreversible cessation of all functions of the brain - including brain stem, is dead." The act is law in 39 states and pending in others. Using the established criteria, no one properly diagnosed as brain dead has ever regained any brain function.

With the idea of brain death fairly clear in my mind, the next concentric circle of this kingdom of living dead to explore was the world of the irreversibly unconscious the realm of the vegetative.

Unlike the brain dead, the vegetative have a functional brain stem. At the core of the upper brain stem is the system of nerve cells and fibers called the ascending reticular formation, a Y-shaped structure that serves as a two-way street to and from the cortex. It adjusts all incoming and outgoing commands from both cerebral hemispheres. The reticular formation constitutes the brain's general broadcasting system. It wakes us up and puts us to sleep, allows information to be stored or forgotten, noted or ignored. Without it, consciousness is impossible, even if the cortex is intact.

Arousal, wakefulness, awareness. That's the activating part of the reticular formation. If the cerebrum's 10 billion neurons were all discharing at once, one would have continuous storms of electrical convulsions. To gain meaning patterns from this stream of information, you need the reticular formation's inhibitory impulses. Nothing, so far, has been able to arouse someone whose reticular formation has been destroyed.

Unlike the brain dead who lie limp as rag dolls, vegetative patients may exhibit bizarre 'decorticate posturing' and spasticity. Their arms and legs contort into 'flexion contractures.' Elbows, wrists, fingers bend in toward the chest - knees are drawn up fetally - toes down. Some occasionally yawn and stick out their tongues, exhibit lip-smacking or chewing movements grimace and grind their teeth - all stereotypical repetitive reflex responses without purpose.

This is a pretty good portrait of Karen Quinlan at the time of the trial. When the media and even the medical professional referred to her as comatose, they were usuing the term imprecisely. They should have said vegetative.

I was surprised to learn that there are about 10,000 Americans living in this kind of black hole of the soul. These are the 'biologically tenacious,' to use Surgeon General C Evertt Koops' term. A crushing financial burden to their families, the typical bill for a year's care is rarely less than $200,000. But worse is the family's uneding psychic pain. When I went to see her, there was no one there. John Jobes thirty -one, told me about his wife. Nancy also thirty-one. Finally he stopped going.

Nancy Jobes, vegetative for seven years was sustained by a feeding tube in a New Jersey nursing home. in 1980 as a pregnant young wife, she was the victim of a tragic set of accidents. First, an automobile accident killed her fetus. Next, during an operation to remove the dead fetus, she suffered anoxia loss of oxygen to her brain long enough to cause enormous damage to the cerebrum. Two years ago John, with nancy's parents and Quinlan lawyer Paul W Armstrong, filed suit to have the feeding tube removed. The Lincoln Park nursing home refused. The family won their case but the nursing home appealed. Not until June 1987 were Jobes and his parents-in-law released from their purgatory. At that time the New Jersey Supreme Court decided in their favor and Nancy will be allowed to die with dignity, as they say, after years of pointless indignity. It has been inexpressible hell for John Jobes.

'There comes a point where you just can't let it go on and on,' he says, his voice low and angry. 'Nancy would never want to be in this state.' Today he is emotionally and financially wiped out. And after seven years it's hard for him to get on with his life. "My mother and father-in-law tell me I should' he says hollowly, "but its easier to say than do."

Even though the AMA has now jugded it ethical for physicians to withdraw treatment from such irreversibly unconscious patients, confusion and controversy over this latest dilemma of high-tech medicine still rage in the courts, hospitals and nursing homes. And the problem, more delicate and complex than brain death will not go away. It's just gathering force.

A number of people are suggesting the Nancy Jobeses or Karen Ann Quinlans, the persistent vegetatives, could join the ranks of the neo-morts. Stuart Youngner - a psychiatrist at Case Western Reserve Medical Center in Cleveland - is one. He thinks society should draw up a new definition of death. "Once consciousness is gone," he says, "the person is lost. What remains is a mindless organism." After the loss of personhood, he says the death of what remains is not the death of a human being but of a thing: 'the demise of a body that has outlived its owner.'

Needless to say this new cognitive death idea has vehement opponents within the medical community. Most M Ds are terrified of it. Dr Vivian Tellis, renal transplant surgeon and co-director of the transplant program at New York City's Notefiore Hospital exclaimed to me that the idea was 'grossly inappropriate.' A dangerous distinction. "If it were instituted, I'd get out of the business immediately."

'It's the Coma thing for real' said another. In the movie Coma, a female anesthesia accident victim is declared brain dead - they pack her off to the nefarioous Jefferson Institute where her body will be maintained artificially until her parts can be harvested and sold. (Neurologically speaking, that's all wrong. She could not have been brain dead. She would be in a persistent vegetative state.)

Many physicians foresee the massive proliferation of "Jefferson Institutes" devoted to harvesting organs from the vegetative dead. There is no end to possible scenarious. Female vegetatives for example - might be employed as surrogate wombs - providing that endocrine balances could be reestablished after the disruptions that often accompany profound brain damage. The vegetatives could even be mated to produce fertilized eggs or offspring. The French, who claim to be horrified at discontinuing treatment of long-term vegetatives - in the same breath advocate using them experimentally.

Society has a ways to go before we set up human vegetable farms, in part because many people superstitiously or not, thinking that the long-term unconscious might someday wake up. Could it happen? It seemed important to discuss this issue with people whose optimism for the unconscious is the guiding principle of their work. The Greenery is such a citadel of hope.

Located near Boston, the 201-bed institution is one of a number of long-term head injury rehabilitation centers. Indeed the Greeneries are flourishing, with branches in North Carolina, California, Texas and Washington State. Coma's Jefferson Institute was on my mind as I arrived at the Greenery's series of garden apartment buildings. There was no huge windowless facades a la Coma. There is no forbidden nurse at the door, anyone can walk right in.

The Greenery gets plenty of business. The National Head Injury foundation estimates that 50,000 people a year who survive serious head injury are left with intellectual impairment of such a degree as to preclude their return to a normal life. Thanks to modern medicine the patients have survived overwhelming brain injuries, but they arrive at the Greenery in varying degrees of unconscious or semi-aware states. Unlike conventional nursing homes, the Greenery does more than feed and nurse these people. It attempts to bring back some awareness through a program of intense sensory bombardment, physical therapy and for those able to benefit, special education.

Upon seeing the Greenery's patients and hearing their case histories - many car accident victims - I vowed always to fasten my seat belt. The patients themselves are inescapably sad. They are the bereft wandering shades of a modern Avernus; some perceiving dimly, some in childlike wonder, others seeing, hearing nothing. Their state was much harder to take than the finality of R.H's brain death.

Rigid in different poses, some resemble fleshy statues partially liberated from their molds: a mad choreography of frozen flexor contractures, seizures feet en pointe. To ease their muscle contractures, many patients are armored in leg, arm and hand casts. Even the unconscious are tied by their foreheads in wheelchairs or strapped to boards slanted up against the walls to expose them to more stimuli.

The staff is committed to searching for signs of life in even the most deserted looking bodies. "We have a mission to try to wake these people up and this is one of the few places that is dedicated to serving this severely underaroused population," explains staff neuropsychologist Laurence Levine.

I took the time to watch their mission in action. Young vigorous physical therapist Karen Giebler introduces Randy who sits speechless in a wheelchair. She presses electrodes against his skin, using electrical stimulation to prime the atrophied muscles of his legs. A construction worker from Oklahoma: he had been hit in the head by a demolition ball that demolished a good part of his left cerebral hemisphere. His wife refused to believe he was hopeless and eventually found the Greenery. Randy was admitted with muscle contractures that had pulled his legs up to his chest and pointed his toes like a ballet dancer's. Giebler transfers Randy to an exercise mat and she slowly lifts and lowers his now uncontracted legs 25 times each. I watch Giebler work a little longer and after a while say good bye to her and to her patient. But there is no response from him as I leave. He stares straight ahead.

The staff members admit it's difficult to keep the fires of enthusiasm burning when there's no response day after day, month after month. Though they all have their Lazarus stories of the hopeless who eventually walk of the place on their own, no one has published any data about these amazing returns in the medical journals and this, to the neurological community is a serious weakness in their presentation.

Yet if there were a new cognitive definition of death; several of the Greenery's patients could be conceived as candidates. I ask Levine "Should death be redefined as cognitive loss?" "Working in a place like this raises questions like that all the time," he says, "profound questions about what a person is. There are patients here who are very dependent, severely underaroused, with little hope on the horizon."

"I've thought about what would happen to me if I wound up like one of them. At this point I'd want to die," he admits. "But my hunch is I'd change my mind if it actually happened. More like I'd not have the cognition to know. What I'm trying to say is I don't have any fixed answers. Some people may believe that these people should be put to death but as a society we can't condone that."

When I bring up the idea of cognitive death to him, Korein argues "To consider a vegetative state as death is not practical. If you pronounce them dead and they're breathing on their own, what do you do? Take them out and shoot them? You can't discontinue their life-support systems sub rosa." Unlike the brain death situation, withdrawing support from the vegetative is a social decision, not a medical one. The physician can't play God and decide to withdraw support.

Pressed about his personal feelings about higher cognitive death, Korein says that once an individual is no longer capable of awareness, is no longer a thinking beinng and is in that irreversible state, "yes, I consider it the death of a human being." But he reminds me that there have been two recorded cases in which persons declared irreversibly vegetative did "come back" - although that return of function 'doesn't mean they dance,' he adds. "They could hardly communicate and do not walk." Furthermore, the criteria for determining a vegetative state are much less established than for brain death.

For background on what those criteria might be, I decided to ask another knowledgeable neurologist. "I believe that the meaning of life is cognition and self-awareness, not merely visceral survival," states Fred Plum, neurologist in chief at Cornell University Medical College - New York Hospital at a meeting at Cornell in Ithaca.

"The concept holds that when the cognitive brain has departed, the person has departed. In my opinion it is acceptable, perhaps even desirable that society come to share this view, but" he is careful to add "that is a personal, not a medical opinion."

I sought out Plum because he is the best there is. Perhaps the world's top expert on coma, Plum is a hybrid of the kindly white-haired physician and Apollonian intellect - elegent, contemplative and analytical. His book The Diagnosis of Stupor and Coma written with Jerome Posner is the definitive text on the subject. Today, with colleague David Levy, Plum has been employing PET (positron emission tomography) technology to peer into the interior of this gloomy condition.

He has been doing preliminary PET studies on the cerebral metabolism of vegetative patients and he and his colleagues are now trying to evaluate the potential for recover of the severely brain damaged who are not vegetative. Using statistical evidence, he's built up rather sturdy predictors of who will do well and who will fare badly following severe brain trauma. He uses a sophisticated computer program that analyzes detailed information on the progress of the severely brain injured.

Within less than two weeks after onset, Plum says about three quarters of the damaged area show clear clinical signs that predict whether they will have a generally good or devastatingly poor outcome. These data are correlated over a period of time, he says "with the aim of eventually producing a one hundred percent prediction of who will do well or, conversely, who has no chance of recovery."

Does that mean you can say with 100 percent assurance after three months that Mr X is in a vegetative state from which he will never return? "No," says Plum. "There will always be head injury cases that defy the odds and recover. Nevertheless, being able to predict with a strong probability gives the family some facts upon which to make a decision," he maintains. His predictions could help a family decide whether to disconnect a life-support system or what to do with a brain-damaged patient who has a living will. Such a personal statement made when the person is in full command of his self-determination serves to advise physicians against ordering millions of dollars worth of needless care for hopeless cases.

Like Korein, Plum think that ultimately it is not the doctor's job to make the decision for the patient. "My facts are an effort to give people enough information so that a reasonably informed layperson can participate in the decision, knowing what the options are."

But over the next 20 years, the overwhelming demand for organs may increase the pressure to simply declare the 'brain absent,' dead. There is already something of a black market for buying and selling organs. if the cognitive-death definition were instituted, organ-merchandising corporations might establish enterprises beyond Wall Street's wildest insider fantasies. The world would find itself in a situation where death itself would be an industry - an economic incentive.

But as Youngner points out this economic pressure is not necessarily bad. "When Columbus sailed across the Atlantic," he says "the main purpose wasn't to prove the world was round. It was to find new territory to plunder. It wasn't the philosophers who stimulated the cognitive death criteria of death - it was those who wanted the organs." We should be careful, he says - that the need for organs doesn't take over completely because it confuses the issue so that we are unable to debate the topic of death in a logical, intelligent way. If the brilliant liver transplant surgeon Thomas Starzl for example - has said that we should take organs from the vegetative, why should we do it? Because their lives are of such poor quality that it doesn't matter or because they're dead?

Even without a shift to a cognitive death criterion, we already face major social and legal questions. "In the case of persons - bodies really - that have lost all individuality or capacity for self awareness, have they also lost their constitutional privileges?" asks Plum. "This question is an artifact of technology. If it weren't for modern technology, we wouldn't be faced with the prospect of more and more very old persons continuing to survive in nursing homes after all shadow of their personalities has left the face of the earth." The numbers of these people will continue to climb and society will have to try to reach some kind of balanced judgment about what to do with those with no living wills.

We also have the emotional stress of treating the legally dead. This fact was brought to doctors' attention by Youngner's powerful essay in The New England Journal of Medicine, "Psychosocial and Ethical Implications of Organ Retrieval." In his article, Younger notes that maintaining bodies for 'harvesting' often requires treating dead people as if they were alive - an upsetting experience for doctors and nurses. They must try to ignore the signs of vitality that bombard their senses and at the same time provide the dead donors with intensive care usually reserved for the living. If a brain-dead donor in an intensive care unit goes into cardiac arrest, for example, alarms ring and medical staff rush to revive the body. Meanwhile a DO NOT RESUSCITATE order might be written on the chart of the living, perhaps even wide-awake patient in the next bed.

Surgery to remove organs also requires hospital staff to suspend their medical instincts. The dead don't usually go to surgery and as Youngner points out, the brain dead wheeled into the OR don't look that different from the living, anaesthetized patients. OR Personnel used to life-saving surgery, upon seeing the removal of vital parts, may be shocked by the mutilation. In some cases of what's called long bone retrieval, one OR nurse told me the surgical team removes the thighbones and replaces them with broomsticks to keep the legs' shape. Another organ-donor coordinator who has logged hundreds of hours in OR's confessed she still can't watch eye removals.

After long hours of 'retrieval' surgery, the anaesthetologist does not of course wake up the cadaver. He simply disconnects the respirator and leaves the room. The remaining surgeons do a perfunctory job of sewing up the body cavity using coarse thread and large needles. And the body is sent not to the recovery room but to the morgue. (Even after being told what has happened to a patient, families sometimes ask the doctors what time the donor will be brought back to his room.)

Youngner has now embarked on a long-term study of health-profession stress and organ retrieval. In his office, looking athletic in chinos and a blue jacket, Youngner has a sensitive face and speaks gently but firmly. "I got an incredibly positive response from OR personnel from that Journal pience," he says. "I don't want to exaggerate and say that they're all terribly traumatized by brain death and the organ retrieval process but most everybody finds it a little uncomfortable, a few find it considerably uncomfortable."

Many MD's dont' really come to terms emotionally with brain death even though they intellectually understand the mechanisms. Attending physicians often balk at writing the death certificate for a person pronounced brain dead.

Faye Davis, director of the New York Regional Transplant Program uses Youngner's essay in some training sessions to sensitize hospital staff. "Sometimes ICU staff complain about taking care of dead people," she says, "when they have so many live people to take of. So we might hold off on a pronouncement {of death} to help them feel they're still taking care of a patient. It's less stressful. But it's hocus-pocus and in a sense they know."

Youngner also talks about the 'spirit' the staff often say they feel in the operating room during surgery: the presence of a life-force there, but sleeping. OR personnel 'often feel a similar presence with brain-dead patients and it doesn't depart until the respirator is turned off.' Families talk about the spiritual entities as well. Sometimes, says Davis "they know when their loved one is dead while we're still figuring it out by the tests. They know he's just not there anymore."

Outside the medical profession, the reaction to brain death is blind fear. "Many people are afraid the doctors are going to grab their kidneys before they're dead," says Montefiore's Tellis. But we shouldn't worry - "In fact, donor cards are you best insurance. If you come into the hospital seriously injured and your survival's in grave doubt, they'll probably give you the very best attention. For your organs sake."

In the midst of these discussions, my mind kept returning to the question "What is a Person? And more important, what will a person be in the future? It's not inconceivable that before too long, brain stem function could be replaced by a computer: for example, a silicon clone of the reticular formation. This autonomic organ could be compacted to the size of a real brain stem and inserted into the head. Then irretrievable consciousness might be made retrievable: the lost person brought back.

In the course of his interview, Korein began to speculate about the value of such a machine-brain cyborg. "If I knew how to make one, I know what I'd use it for; for someone with an immediate-memory deficit, a patient who will forget he has met a visitor after that person steps out of for a moment and returns. If you could create an external visual memory system for him, then when someone walks into a room - zip - it is recorded into the machine's external memory. Then if the person walks out and returns, the memory would compare the person who left with the person returning and report to the brain of the memory-deficit patient, You already saw this guy."

This, then brings up another basic question. Where is the mind? "The brain is something you can touch, squeeze and do experiments on. The mind has other properties, but it's certainly related to the brain. I don't know any mind without a brain. I know lots of brains without minds. I'm sure you've met them!" Korein laughs. "Actually, the mind must evolve in some way from self-reflective processes. Living beings all have this ability to look upon themselves. In one-celled animals it's an enzymatic system, a positive feedback. In humans it's the ability to put together a set of stimuli, store them, look upon them, feed on them. And the repetition of this is, I think, what results in a mind."

I asked Youngner to contemplate the implications of the computerized mind. What if one could decipher the program of a person's personality and transfer it to a computer that would store the memories, react with the same 'emotions?' Could one argue that even if the human had forever lost consciousness, he'd still be alive because this computer was standing in?

"I'd say that wouldn't be a person but a robot," he decides, considering the options. "Okay - what if you took the brain out of a body and put it in a solution with a communications system? I'd still say it wouldn't be a person because to me a person is - at bottom - a biological entity. Our identity is very much tied up with our body and we have an idea of who we are based on our physical attributes outside the brain."

On the other hand - he takes the opposite view without much painful dissonance - "if you have this brain in a jar - say it was my brain - and it said "I'm a Pittsburgh Steelers fan and I'm upset they didn't have a good year," then it would be hard to dismiss the idea that Stuart Youngner is alive although his body's gone. It might be the presence of an identity, but it's not a human being. It gets pretty tricky."

So the question of death ultimately becomes the question of what is life. After almost 20 years of research on death, Korein is more excited these days about life. "The process of being born is, in a sense, just the opposite of dying. When does the human being begin? At fertilization? When it is an embryo? There's a constructive phase between 10 and 20 weeks of fetal life when the neurons are being produced and organized. The fetus moves as early as eight weeks," Korein says, "but that's spinal cord activity, a vegetative function. Around 20 t0 24 weeks, the cerebrum starts to show signs of electrical and synaptic activity."

"Then," he says "you could say it's the earliest possibility of cerebral-mental life. It hasn't the ability to work like a normal three-day old baby, but the pieces are in place, starting to grow and connect. That's the beginning of a person's life - brain life."

In tracking the dead and the near dead, I was haunted - so to speak - by the words of Carleton Gajdusek. The Nobel Prize winning virologist is famous for his discovery of the slow virus in the Fore people of New Guinea. During his research, he intensely observed their mortuary ritual of eating the brains of dead family members. It was an expression of love for their dead relatives. "They had no tear or reluctance to look at the brains or intestines of their kin," Gajdusek told Omni. "They always dissected their relatives with love and tender care and interest." It was Gajdusek's opinion that were it not for the viral infection in the tissue, eating brains would have "provided a good source of protein for a meat-starved community". Not long after I started this story, I went to hear Gajdusek speak at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York. During the address he spoke of the 'neocannibalism' of modern medicine.

With the great advances in life support technology and organ transplantation, the dead today do indeed have much 'protein' to offer us - in the form of their organs and body parts. We are the neocannibals.

Unlike Fore Culture however, Western society has a horror of the dead. We prefer not to think about death at all and when forced to deal with it, we do so as hurriedly as possible. We have no new death rituals and little understanding of neocannibal practices. And our old superstitions may work counter to a true understanding not only of death but perhaps of life too.

The radical outspoken Dr Tellis is concerned with life; the hanging-by-a-thread life of someone waiting for a heart or liver or kidney. He has no patience with families who refuse to donate the organs of brain-dead kin. "The social climate surrounding donation today should be reversed," he told me as he waited at Good Samaritan Hospital that night for the rest of the transplant surgeons to arrive for RH's organs. "Instead of feeling good and righteous about donating," he said "it should enter the collective unconscious that you feel bad if you refuse. The family who refuses to donate a dead relative's liver should be told they killed the waiting recipient."

Slowly we are coming to terms with brain death and the new life that it offers. What we decide to do with the life in limbo that is the vegetative state remains to be seen. But it is better to betgin to think about it than to ignore the increasing price we have to pay for this most unblessed death on the installment plan.

https://youtu.be/MGXSPf9b-xI

>The family who refuses to donate a dead relative's liver should be told they killed the waiting recipient.

When they took the unjabbed off the organ recipient list, I took myself off the organ donation list.

>society will have to try to reach some kind of balanced judgment about what to do with those with no living wills.

(we are here)

Great work mate. Chilling.